Where the Spirit Might Dwell

In undoing the architecture of my late parents’ everyday lives and deciding what to discard, was I committing a small act of violence?

I STAND IN the mouth of Guardian Storage Unit No. 12104, on a swath of land just east of Pittsburgh. It is a sunny August afternoon in 2020, the height of the pandemic. It is 20 months since my mother died of complications from dementia and nearly five years since Alzheimer’s Disease ended my father.

This is the last of 13 years of visits to this storage space for me, and my mind is turning to some of the others. My stops here tended to come in waves that mapped directly onto the inflection points of my parents’ decline.

- August 2007: Move stuff from their longtime home to this space, just up the road from their first “independent living facility,” with my mother insisting they will bring folding chairs on summer afternoons and sit with me as I sort the possessions they accumulated over a lifetime.

- June 2012: Bring more of their stuff here, including my father’s prized and longtime desk, untouched since a fall cracked his head open and sent him tumbling into the assisted-living facility where my mother is about to join him. He has no room for a desk in the new place, but that is OK, because he neither needs a desk nor knows he ever had one.

- December 2019: Sit in the cold unit on a dark winter afternoon with my two sisters, going through what we can by the light of battery-operated lanterns and making joint decisions about what will end up where.

And now this August day, on which even the storage space itself seems saddled with nostalgia — another way station in my parents’ journey from competence to decrepitude to absence, another waypoint for the things they left behind.

The unit is all but empty now. Just outside it, I sit on the edge of my father’s desk and await the arrival of an outfit with the unlikely name “College Hunks Hauling Junk.”

And I have this persistent feeling, as I tend to this agglomeration of my parents’ worldly goods, that I am somehow doing something awful.

ALMOST THREE DECADES AGO, something fascinating unfolded in Philadelphia that haunts me to this day in the manner of a friendly ghost.

An elderly woman named Elva Norris, who lived in a second-floor apartment near downtown, had died in 1993. She’d been married to a pharmacist whose family had run a drug store and soda fountain beneath the apartment from 1902 until June 1953, when Charles B. Norris boarded up the shop and they decided to travel. When he died in 1975, she used the shop as a sitting room. She’d read magazines, hang with the grandkids or grab an unsold greeting card to send to a friend. Outside, the world went by. When she died, her children sold the place to an architect who started renting it out as an ice-cream shop with a wonderful name: the “Phantom Fountain.”

The minute I heard about this, as a young reporter in Philadelphia, I knew I had to write about it. I remember stepping inside, looking around and feeling overwhelmed. Around me sat the consumer society of another era, one when my parents were a young couple with two little girls. There were 1950s pulp novels and gallon jugs of unused Coca-Cola syrup. Stacks of prescriptions dated to 1910. One rack was full of envelopes of “Phototone Album Prints” that had been dropped off, developed and never claimed.

What I remember most was thinking: There is something more here than simply cool retro stuff. The people who last touched it — who chose how to arrange it, who used their executive function to make a years-long series of daily-life decisions about it, who unknowingly committed it to posterity — were long gone. And yet, in the way the shop was preserved, something of them remained.

As I interviewed Martin Rosenblum, the architect who’d stumbled upon this treasure and, mercifully, saw both the historical and spiritual value of what he was gazing upon, I asked him the main question on my mind: Why did you decide to keep all this the way it was? His response has stayed with me.

“The idea of taking something like this and being a part of its dismemberment, I couldn’t do that.”

This man knew what was intuitively clear to me, though I didn’t quite have the words for it yet: The essence of the Phantom Fountain was not merely the items it contained, but the frozen moment that had kept them there. In such moments, magic lurks.

THOSE OF YOU who have lost someone, and in particular lost someone to dementia, know that the things left behind can be fraught. Each piece can have a weight far more than its physical weight and a value far more than its monetary worth. The tiniest of items can be ballast that ensnares you and fixes you to a certain point in time, to people, or to both.

My experiences come from a curious combination of events. I had parents who came of age at the cusp of the consumer society, a period when a rising tide of disposable items arrived in the matter stream of American life. Landfills swelled. Hoarders came into their heydays.

But my mother and father, as university academics — and the first in each of their families to go to college — also recognized the value of curation and of capturing breadcrumbs from the trail they traveled through their lives.

And travel they did: across continents and nations, across an astonishing variety of interests and passions from books to Asian art to Danish furniture to tiny bars of soap from hotels long forgotten. Archivists at heart, they saved all their appointment books across the years. She saved clippings from catalogs of things she’d bought for her family at Carter-administration Christmases. He saved selected cords from two generations of discarded appliances in fervent hope, I think, that something at some point would find itself in need of an electrical resurrection.

Lest you think they were hoarders — though that gene does, I think run through our family, and I speak from personal experience — they generally kept this stuff immaculately organized until their last demented years. There was a lot of it — a lot of it — but it was hardly chaos.

So when they decided to downsize upon leaving their house of 42 years (the house in which I and my family now live, still sifting through their stuff, though that’s another story for another day), a lot of things landed in this storage space.

Seeing one’s childhood home dismantled, stripped of years of decorating and storage decisions, is something many people face as young or middle-aged adults. Some are doing it under circumstances of grief; for others it’s optimistic and the beginning of a new chapter for a parent or parents. But whatever the scenario, it can be emotionally disruptive, and for me that wasn’t mitigated much by the fact that I was moving in. Yet somehow there was comfort in the fact that — because my parents were overwhelmed at the amount of stuff they’d accrued — it would still be around and available in the storage space if they wanted to revisit it (though they never did).

So Unit 12104 became a place where time kind of stopped, a frozen moment not entirely unlike the Phantom Fountain. Rarely did I visit it to extract; the visits were mostly to insert. And in there sat hundreds, even thousands of tiny talismans, things connected to experiences and people and places and times. You don’t think inanimate objects can be ghosts? Try visiting a filled-to-the-metal-ceiling storage space after a loved one is gone and report back. I’ll be interested in seeing if your thinking has evolved.

On this final day in 12104, I feel the ghosts more than ever. They are padding through my head, gently but persistently, as the final push of countless decisions in miniature — Save? Donate? Give to relatives? Discard? — washes over me.

This feeling is not because of the things themselves, though fascinating and contemplation-worthy they are. It’s not even because of the many tiny decisions I must make, though those feel freighted, too: In some cases I am perhaps the only person left on the planet who recognizes, say, the cheap souvenir pin obtained from the tractor factory we visited outside Luoyang, China, during a cross-country train trip in 1980. How can I get rid of that?

It was more than all that. To me, the things were imbued with the choices my parents made as they moved through their lives — choices that are represented by these items.

There are schools of thought in some faiths that the trappings of the everyday — the pieces of life that go unnoticed and unrecognized — are actually the holiest things of all. I’ve always appreciated that supposition. And if there’s anything to it, then each of these items — the precious and the entirely disposable, each there because someone decided to obtain it and decided again not to discard it — has a bit of magic to it.

I’m not naive. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that a storage unit full of a previous generation’s junk is a temple. But honestly, standing in this metal box, alone with the final items to clear out — a couch I grew up napping on, a fraying Scandinavian chair where my mother read for perhaps 10,000 nights, and of course my father’s desk — I wouldn’t not say that, either.

IN THE TV SERIES “American Pickers,” a show that could not exist without the accumulated excess of American consumer lives, each treasure-hunting trip across the republic typically features some kind of reveal. It’s that moment when a basement light is turned on or a shed door swings open, and those accumulations of someone’s lifetime are exposed to the world and to the very excited hosts.

There is no excitement in Guardian Storage Unit 12104 on this particular afternoon. There is only me, standing in the semidarkness, lost in a pile of thoughts as miscellaneous as what I’d spent the past few days going through and purging. The file cabinets full of professorial ponderings are gone. The boxes are all dispatched. The decaying furniture has been broken into pieces and is en route to houseware heaven.

Only the biggest, clunkiest items remain, the ones I can’t fit into our car. That includes my father’s desk. For one of my final acts of this postmortem responsibility, I go through the drawers. This is the moment when I come up with the question that tops this essay: Am I, at least theoretically, doing a bit of violence here?

Desks are colonies of curation. In few other places do you see, in such a distilled manner, the way someone arranged their life and their tools and the tiny things in which they found value. It’s philosophy through office supplies.

My head fills with memories of my father at this desk and the one before it. Occasionally I’d bound downstairs to his study and find the contents of a couple drawers spread across the desktop and realize I’d caught him in the middle of his periodic rearranging. I’d know that it was, mysteriously, time for the blank 3x5 cards and round orange stickers to move up a drawer, for the can of rubber cement to be redeployed, for that magical rubber stamp that somehow impossibly bore his signature to be wiped of ink and replaced carefully in the organizing tray.

I sift through this ephemera and box it up, saving more than I throw out. I am, after all, my parents’ son.

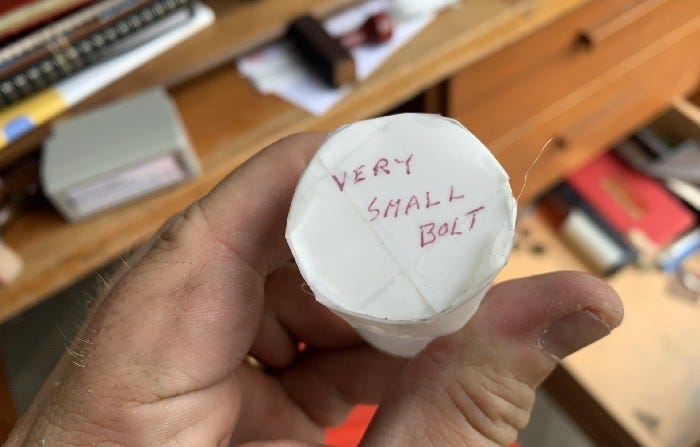

The desk is mostly empty now — I think. I give it a semifinal check, running my hands across the back of the drawers. Then, in the recesses of a bottom drawer, I feel something slightly stuck — a small canister of some kind. I pull it out and realize it is a cut-up part of a toilet-paper roll, wrapped in stationery and sealed carefully, impenetrably, with tape. As I hold it, I feel something small rattling inside. I wonder what it is.

I needn’t have. My father, who was nothing if not a labeler, has written three words upon it in red ink, in block letters: VERY SMALL BOLT.

I laugh aloud and am somewhat startled when it reverberates through the metal-lined Unit №12104. Outside, I hear a truck rumbling. The College Hunks Hauling Junk have arrived. As I instruct them on how to load the final items onto their flatbed, I clutch the VERY SMALL BOLT. I don’t want to let it go. I feel it kicking around inside the preposterously secured toilet-paper roll.

The College Hunks pull away. Our junk has been hauled. I stand outside my old friend 12104 and watch my father’s desk, and all the ghosts it contains, drive through the exit gate and recede down Old Freeport Road. I wonder if it will continue to exist somewhere.

I shake the VERY SMALL BOLT, think of my parents and start to make my way home.

Ted Anthony, a journalist based in Pittsburgh and New York, has reported from more than 25 countries. He is the author of Chasing the Rising Sun: The Journey of an American Song. He tweets here, Instagrams here and collects his writing here.

Further reading by Ted Anthony:

©2023, Ted Anthony.