The Century Club

Nature, memories and the lonely death of Jay Gatsby. Notes from the woods on my father’s 100th birthday.

LISBON, Ohio, 9/1/22

There is a vast difference between being alone and being lonely. My father knew this, I think. He was an introvert by nature who chose somewhere along the way to become an extrovert and engage with the world.

Exactly when this choice was made, I am not certain. Perhaps it was when he realized that he wanted to teach; perhaps it was when he or someone else realized the quiet leadership capacity that he possessed. And for one reason or another, he began to turn outward. He once told me something to the effect of this — that when he and my mother met, she was an extreme extrovert and he was an extreme introvert, and they each began drawing the other toward the middle.

I don’t know if I believe this entirely. Her extreme introversion at the end of her life (which I witnessed), and his apparent engagement with both the natural and human communities early in his life (which I was not there for but saw through photos and his own recollections) suggest a more moderate state of affairs on both sides.

Whatever the case, my father was in many ways a man alone, though casual acquaintances would probably not concur with that assessment. Whether life led him to this or whether it was endemic, I do not know and never will.

On this day, precisely 100 years after my father was born in Cleveland, Ohio, I am both contemplating loneliness and, by my own choice, alone. I’m sitting at a picnic table outside a cabin in the woods — woods that are, quite appropriately, about equidistant from Cleveland, where he spent the initial years of his long life, and Pittsburgh, where he spent most of the final 50 years of it and where I was born and now live with my family.

Also appropriate: The nearest town to this cabin near the Ohio-Pennsylvania border is Lisbon, also the capital of the country from which the Anthonys, then the Antonios, originally hailed.

I have chosen loneliness on this Thursday in late summer — a weekday, a workday where I should be at my desk — to pause and reflect on my father’s life and my memories of him on this auspicious and utterly artificially constructed day.

We human beings find coherence in the world by breaking it down into tiny and right-sized chunks: a year, a decade, 25 years, 50 years. The century is the gold standard of this propensity for segmentation. I think that’s because it’s the largest understandable, digestible, round number that has bearing on our lives. The next really big round number is a millennium — 1,000 years. That is simply too vast for most of us to get our heads around. When 1999 and became 2000, and I was there covering it (whatever “there” means in such a context), people seemed far more focused on and intrigued by the end of a century and the dawn of another than they did by its simultaneous millennial equivalent.

One hundred years is something that manages to be both adjacent to right now — just beyond the reaches of living memory — and yet also incalculably distant, hinting of and connected to other eras to things now completely enshrouded by time. Once, when we were at a monastery in northern Thailand, we came upon a sign both depressing and exhilarating in its wisdom:

“Cut yourself some slack. Remember, one hundred years from now, all new people.”

The truth, I suppose, is that I am lonely without my father in the world.

The segue between him taking care of me and me taking care of him was so gradual, so seamless, that it was difficult to notice in real time. Even as his body and mind weakened bit by bit, moment by moment, and even as long and complex and multilayered sentences ebbed into single-subject/verb/predicate utterances (and eventually barely even that) he still tried to take care of me even as the universe, his stern editing taskmaster, truncated his Faulknerian (sometimes even Joycean) musings into Hemingway parodies.

I’d see him struggle to find ways to give things. Sometimes they made sense. Sometimes they didn’t, or were outdated from that proclivity that Alzheimer’s possesses to compress time and make all our yesterdays seem like right now.

“Do you have secretarial help?” he’d ask me. “What is your base of operations?” he’d say, trying to push away dementia’s mists and work out how it could possibly be that we lived in our house, his house, five miles away, and yet also in Thailand, which was so familiar to him after many years there and yet now so distant. “I think I may move back to Bangkok one day,” he’d say as my mother sadly shook her head. And he’d say it as if it were just as likely and feasible as another favorite mantra of his: “You and I should go get a sandwich and a beer sometime,” which started out as a memory lapse a few days after we had done just that and, by the end, was as unlikely an ambition as his dream to move back to Thailand.

I miss it all. Even the frustrations. Even the excruciating parts. “I’m sorry, Ted,” he’d say. “You shouldn’t have to do this for me.” That was when I was giving him haircuts. I even miss the final days when his organs began to collapse and his skin was as thin as the edible rice paper that comes wrapped around chewy candy in Asia.

But I think what makes me the loneliest of all is the fact that in some weird way, those final years of decay and what he called “decrepitude” stole from me the years before the slow decline. Even now, seven years after he died, I have trouble accessing those times. I mean, I can access them intellectually. I have memories and photographs, and I know what happened and how they were to me. But I find that I cannot feel my parents anymore.

It is as if the memories of more vibrant parents are locked in a room in my brain. And I roam around the other rooms and hallways and common areas, and those places are cast in shadow, bathed in the blue light of grief. But that one room, the one with the warm yellow orange light peeking out from the crack on the floor, is inaccessible to me. I know it’s all in there and intact, but I simply do not have the key.

And without new material to somehow overwrite this grief or at least remand it to its proper place in the proceedings, I have no recourse. Or do I?

Into the woods with me today I have brought two plastic crates full of files — actual paper files of the kind that I rarely use today as I continue my years of assembling a paperless archive of my own affairs (not quite paperless enough, my family might say).

The first crate is full of things that I have mostly — with a wonderful couple of exceptions — already seen. It is reminiscences of moments in my father’s life. Some of it was written contemporaneously (“Interlude in Burma,” his essay about a stop during an early 1960s train ride along the Irrawaddy River, was published in the University of Michigan quarterly in 1962) and some of it was written and sometimes published much later (“Baseball in the Street” appeared on the op-ed page of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette around the turn of the 21st century and earned him an effusive letter from famed coroner Cyril Wecht on Allegheny County letterhead).

But on balance, it is a boxful of writing by a man who knew he was approaching life’s final chapter and wanted to transfer his knowledge and memories from the locked room of his brain to venues more accessible to progeny and posterity.

Folders are titled variously: “Autobiographical Pieces.” “Reminiscence Book.” And my favorite, “Inkblots on the Sands of Time.” It seems clear that he wanted to compile these pieces into a book, and he wanted to be remembered — or, at least, for these slivers of his life and times to be remembered.

The file tab labels, it’s clear to me as the person who administered and helped maintain his late-in-life computer equipment, are from his later, better inkjet printers. That firmly places these efforts in the window of his final high cognitive period from about 1999 to 2007, when he and my mother decamped to an independent living facility in Aspinwall called Lighthouse Point that within a few years produced a life that was decidedly less independent.

In this crate, I find multiple copies of pieces in various states of refinement and revision. One piece I’ve known about for years chronicles his chance encounter with his childhood hero, Charles Lindbergh, on a night flight from Tokyo to Honolulu sometime in the late 1960s or early 1970s. Attached to one version of it is a delightful note from Lindbergh’s daughter, Reeve, to whom my father had sent the piece. His recollection of the flight and of the Lone Eagle reading quietly on the plane, illuminated by the light over his seat is, the Lindbergh offspring tells my father, a moment that feels more real and authentic to her many years after his death than all the accolades her father received.

Quiet and intimate moments, it seems, can summon a man back from eternity even more effectively than fame and tickertape parades.

My father loved the natural world at a depth and with a fervor I have never matched, at least not yet. Along with his handiness around the house and his understanding of how to fix things, it is the thing I wished I had absorbed and inherited more from him. He offered it freely, I think; I just never took him up on the offer. So it feels appropriate, somehow, that I am here in the woods, enveloped if only for this day.

He had a book when I was small, a large green volume that identified Pennsylvania’s trees by their leaves. He used to take me around the woods in our backyard, pointing out which tree was which. Mostly, I remember that he permitted me to eat the leaves we pulled off of the big sassafras tree. He’d lift me up, and I’d pick them and crumple them, stuffing them gluttonously into my small mouth.

Two summers after he died, I came home from Thailand, where we were living at the time. Alone in the house for a week, I saw the big green book on the shelf and pulled it out to have a look. What I found inside was a gift.

Between many of the pages were dried leaves that he had found — some of them at least presumably from our own woods. And tucked into the volume is cross-referenced evidence that he had been here on this land and found these trees.

It was as if he was speaking to me. He was gone, but here was new content. He was still managing to teach me.

This is perhaps part of why I am here in the woods and not, say, at a beach or in a city somewhere. When you venture into nature — not nature like the woods behind our suburban house in our carefully carved-out subdivision, but nature that is largely away from the built environment and existing largely unchecked and unrestricted — the rest of the world tends to fall away, particularly if you turn your back on the ingenious and infernal devices and screens that mediate our world in 2022.

I believe that the clarity this can provide, even for a few short hours, can pull me back from the closeup shot of my parentless life and offer me briefly an establishing shot of the universe that can bring me closer to people who are gone — to this man who arrived 100 years ago today.

In the early afternoon, I’m sitting here at the picnic table writing, the cadence of daytime crickets in the background, when I see a small bug of unknown provenance crawling across the wood. It is an odd-shaped creature, not a flying bug. It shape is unfamiliar, but it does not seem particularly menacing. I watch it for a while, then return to my writing.

Five minutes later it is back, scaling the sheer cliff of my notebook and crawling across the page before ambling off again. Through the afternoon it returns a smattering of times. sometimes crawling, sometimes sitting and taking stock of me. Finally, when I’m about to cook dinner, it disappears for good. I look up and the sun is peeking through the trees.

The second box is the one I’m really excited about. This is one I discovered unexpectedly about a year ago, one I didn’t know existed.

It is a blue plastic crate containing folders of his “commonplace books,” from one that began in June 1970 to one he started in December 1992 — 10 thick folders in all.

Commonplace books are an idea centuries old, left over from the time when if you saw an interesting thought somewhere, you copied it down to make sure it was preserved. They’re scrapbooks, essentially — places to stow interesting quotes from various sources, mostly, but also match covers and menus and quietly noteworthy ephemera that one encounters along life’s paths. My father always had a few around, but I never realized how consistent he was in keeping them.

So when I found these, I decided two things: I would get them scanned for my sisters and me, but in the meantime I would save them to mete out to myself, parsimoniously, for tiny visits with my dad. And remarkably, given my lack of self control and many things throughout my life, I have until this day looked only at the first few pages of the first. earliest one.

Why is this? Because aside from miscellany, of which there is much since both my parents were neither minimalists nor reticent, this is the only original material I have of my father’s that I do not already know inside and out. In short, if I want to have a continuing dialogue with my dead father, these old words are probably the only new words left. After reading his letters to his mother from Afghanistan, from Thailand, from Singapore and China, after reading the musings and recollections he wanted others to notice and remember, I now have before me a carton of thoughts that he preserved for himself — for his own edification.

What’s more, they are thoughts that coincide with my upbringing almost precisely, from 1970 to 1992. These are the words and the clippings and the curated materials of the father I knew, the one who raised me — not those other iterations or even the later recollections of those other iterations.

I open the first book. I start to read. I see a few things and then I close it, place it back in the folder and put it away. Dusk is falling in the woods on my father’s 100th birthday. Beside me on the picnic table outside the cabin is a box of him yet to be discovered. Echoes of a dead man.

I make a decision. I decide to wait. His voice is here with me now already in the crickets, in the rustle of leaves in the trees, in my own head.

I do not need these words yet. Someday I will. That day is still to come.

By some accounts and estimates, this last week of summer before Labor Day in 1922 was the moment that one of the most momentous sagas in American literature came to its sad end.

As the fictional summer of 1922 waned, the lonely and striving James Gatz — who built himself into Jay Gatsby, a tragic figure eaten by the rising beast that was early 20th century America — fell dead in his mansion’s gleaming pool, shot down by an auto mechanic named George Wilson for a killing he didn’t commit.

“The Great Gatsby” came out in 1925. But Fitzgerald always said the events took place in the summer of ’22, the weeks and months before my father was born. And my father loved “The Great Gatsby” — the Robert Redford-Mia Farrow movie — almost as much as he loved “The Sting,” which came out at almost the same time in the 1970s.

For my father, in both cases, I think it was about the music. While he loved Nelson Riddle, it was Scott Joplin who stuck in his brain, who took up residence in his fingers when he sat down at the piano through my childhood.

Since my father has been gone, for some reason I’ve come to associate the melancholy summer of Gatsby with the event at its end, my father’s birth.

Both were Midwestern men who dreamed of things far bigger than where they came from. Both wanted more, and struggled to figure out how to achieve it. And both were I think, both lonely and alone — 20th-century men navigating forces and progress and expectations that no generation previous had ever faced.

The fictional Gatsby, and perhaps Fitzgerald himself, tried to find anchors in the time around after the Great War, and you could argue that both men lost their way in the confusion and fragmentation that followed. My very real father, born at the end of that summer 100 years ago today, had to navigate through World War II (he wanted so badly to serve, but couldn’t because of his eyesight) and the decades that followed it.

But Gatsby chose emptiness and falsehood and conspicuous consumption to palliate his loneliness, and it ended him. My father, I think, while never conquering his loneliness and the unrequited wants of his youth and middle age, chose collaboration and contemplation and engagement with the world rather than greedy attempts to conquer his corner of it. And by the end of his life, when his brain began to melt, he had become someone who knew who he was, which Gatsby never did.

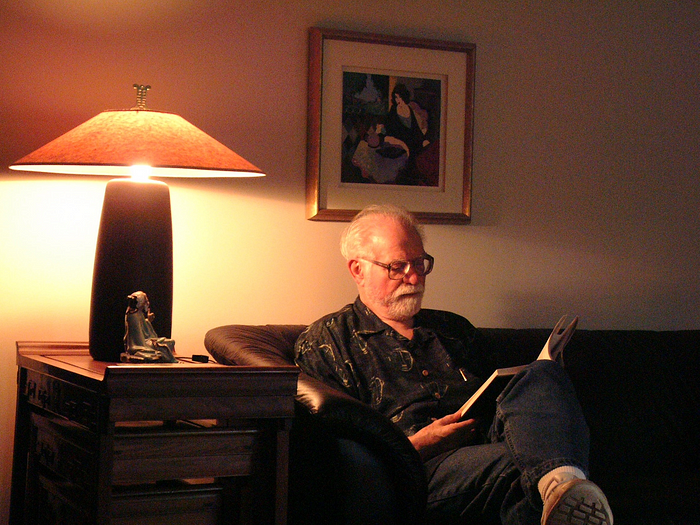

When he and my mother moved out of their house in 2007 and we moved in, my father sat down with me and we talked about the property that he and my mother had bought and built on — his version, I suppose, of Gatsby’s mansion. He spoke eloquently of the woods behind the house, of the study where he could be himself — alone without lonely, I daresay.

Most of all, though, he spoke of sitting in the living room, reading and looking out the picture window and seeing the world go by — the people, the cars, the animals, the changing seasons.

That’s how I picture him now — in sped-up time from, say, 1980 onward: a man who chose the world over his own mind, who chose to go see what was out there rather than, like Gatsby, expecting it to come to his door and genuflect in his presence.

And strangely, tonight, in the dark woods surrounded by the nature my father so loved, I see two tableaus in my mind’s eye.

The first is Gatsby, in the form of Robert Redford, standing at the edge of his opulent mansion in “West Egg” on Long Island Sound, gazing at the flashing light across the water that signaled what he so desperately desired but could never have — beating on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past, as the novel says.

The second tableau is my father, sitting in our living room, the seasons and the world passing in front of him as his beard grows wider and his mind grows foggier.

He is thinking of the world that he and my mother went out into and made a bit better. He watches gingko leaves fall and turn yellow, chipmunks scurry by, deer and turkeys and neighbors entering and exiting the proscenium. He thinks of his children and grandchildren and frets about the future. But overall, he is optimistic.

He and I shared a love for the past, but he would not wish anyone trapped in it. Go forward, he’d say — softly, mindfully, kindly, but go forward. And so I shall.

Happy Birthday, Dad. Let’s talk again soon.

Ted Anthony, a journalist based in Pittsburgh and New York, has reported from more than 25 countries. He is the author of Chasing the Rising Sun: The Journey of an American Song. He tweets here, Instagrams here and collects his writing here.

Further reading by Ted Anthony:

©2022 | Ted Anthony